Dan Winters’ images are iconic; and it’s not just because he photographs icons. The magic of a Dan Winters portrait is it’s authenticity. His pictures have a soul. They invite the viewer to connect with people in a very real and personal way. In a media landscape overflowing with “less subtle” imagery his always seems to stand out. It’s a talent that certainly hasn’t gone unnoticed.

For over three decades he has created compelling images of the world’s most familiar faces and has amassed a list of accomplishments too long to list in this introduction. His images are associated with the best in magazines, book publishing, and fine arts. He has won over a hundred awards for his work and is considered by many to be an icon himself.

I recently interviewed Winters over the phone. We begin talking about a recent shoot he did for Wired magazine that involved both still and motion components…not to mention one of the funniest people alive. We continue on to discuss some fascinating points about his career and craft.

Seckler: Let’s begin discussing the still and motion shoot you did for Wired Magazine that was created for publication in print and on the iPad.

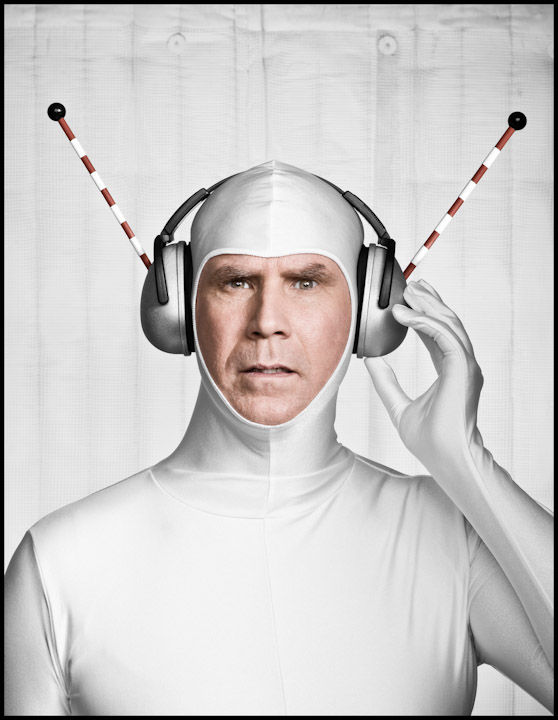

Winters: Wired’s creative director Scott Dadich has been working with adobe for over a year designing software and interface to create a version of Wired designed specifically for the ipad. It’s a fully-realized, fully-designed magazine. It opens up many new possibilities for information delivery. In the third iPad issue there is a feature story on Will Ferrell. It is a light-hearted look at various technologies that were promised but never came to fruition. Jet packs, food in pill form and so on. For this piece I created four short films that were basically motion versions of the still images used to illustrate the feature.

Seckler: How much time, from start to finish, from conceptualizing and designing the sets, to building them, and then to doing all the post work did this take?

Winters: I spent hundreds of hours working on these. The folks at Wired chose several of these failed wonders to focus on. Scott and I settled on five. We discussed treating the visuals as tests in a lab environment with Will [Ferrell] conducting the tests. Once the approach was agreed on, I began the process of creating the world where these vignettes would live. I designed a large set in which all of the images could be made. I drew up a set of plans with all dimensions, material and color specifications. The specs were then sent to the very talented Ed Murphy and OT Ashton at Artworks Hollywood. OT and Ed began prop shopping and I realized early on that some of the key props that I had imagined didn’t exist at the prop houses of LA. I began the process of building by hand those props at my studio in Austin. I then shipped those to LA for the shoot. Scott and I had a conversation with Matt Labov, Wills publicist to broach the idea of generating motion content in addition to still content for the story. Initially Scott asked Matt if we could shoot Will “screwing around” on set.

His publicist seemed amenable but insisted that Will have approval. I think as time passes this type of shoot will probably become more common place but these are uncharted waters at this time. I realized that this opportunity could be much more than just Will “screwing around” so I decided to make these fully flushed out shorts.

I got as much footage as I could on set in LA. I focused on all of the stuff that involved Will directly. It was pretty ambitious to try and pull this of. I would first light the still images with strobe and shoot them. Then, move out the strobe equipment and walk in the hot lights and light for the motion, work hard to be true to the lighting used for the stills. I would then get Will back into position and direct the motion portion. Once I had covered the scenes in LA I went back to Austin where the majority of the work took place. I spent two weeks on additional photography. I didn’t have the time in LA to do any insert shots with Will so I had to replicate the LA sets at my studio in Austin and hire hand and body models in wardrobe to produce the additional footage needed. I also did all of the graphics that appear in the shorts. Graphic design is one of my passions and I really enjoyed this part of the process.

I also used several miniature sets. A rocket in its silo. A giant tower that served as Ferrell industries headquarters as well as a miniature of Ferrell’s aerospace division. The miniature construction was incredibly time consuming. The rocket miniature which measured 45” x 36” inches required three full days of construction time for three seconds of screen time. I had to call in favors for all post-production. Doug Halbert at Imperial Woodpecker in New York helped bring the project together. He had produced several of my music videos in the past. He put me together with Dan Oberle at the white house in LA. Dan did a great job cutting and Clark at Company 3 did an incredible job with the telecine. I ended up giving away 8 thousand dollars worth of prints to all of those directly involved with the post-production.

Wired couldn’t afford to produce the films properly so I had to beg borrow and steel and spend my own time and money on them in order to see the project through. I still feel that with more time on the shoot day I could have brought them closer to my expectation but I’m happy with the final pieces as they stand.

Seckler: Tell me what the response was like.

Winters: I believe [I] handed them something that they never could have imagined would come out of that shoot.

Seckler: You’ve clearly been shooting motion yourself, could you share your thoughts about the fast-paced phenomenon of still photographers shooting motion.

Winters: Hi-def cameras have been around quite a while. And it seems like this really weird phenomenon is happening. Because the digital SLR exists, and can generate both still and video content, add to that there is simultaneously an outlet; photographers are now directors. I think the outlet is what’s determining expectations. Historically whenever new technology comes around, people scramble trying to figure out how it’s going to be used. For so many years, still photographs have been in magazines. The still photograph works for a reason. The viewers ability to ponder and scrutinize a moment can only exist in a still image. The photograph of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima is a perfect example. There’s also film content of that identical event, where the army photographer was literally standing right next to Joe Rosenthal filming the event, but it doesn’t have nearly the same impact as Rosenthal’s still image.

Seckler: So many people say that there is a signature to a Dan Winters photograph, what, in your mind, is definitive of a “Dan Winters” image?

Winters: When I started out in the ’80s I was shooting for newspapers. I really wanted to do magazine work so I would utilize my newspaper assignment opportunities to try and understand my working method. I started to bring lights with me which at the time was not common in the newspaper world.

I began shooting my portrait assignments with large-format and medium-format systems. I began trying to create for the paper, something that was more along the lines of what one would generate for magazines. When I moved to New York I tried to make pictures that weren’t like the pictures I was seeing. Partially because I wanted to challenge myself, partially because I felt like a unique voice would be sought out. If you look at the magazine photographs in the late ’80s, the early ’90s that I was making I think they looked different to some degree than a lot of the work being published. It was an exciting time in magazines. I was really trying to push the edges of the frame, doing really kind of deadpan stuff. Very studied, meticulously-composed pictures. Frames within frames, really compressed lighting. I was trying to keep it simple. I was trying to make things that seemed a little bit more timeless or lasting but odd at the same time. There’s also a specific emotional range that I like to work with. I find when people get quiet and reflective, there’s a catharsis that can take place. The viewer doesn’t feel intimidated. If the subjects eyes are averted, rather than making direct contact, I believe the viewer feels more comfortable looking at that person and studying them and feeling, not necessarily voyeuristic, but not feeling shy or reluctant to scrutinize the subjects physical self. Over the years I keep trying to refine my work and allow it to evolve.

Seckler: How did you gravitate towards doing the portrait work that you’re most well-known for?

Winters: Well, first and foremost I would say that if you asked anybody in the magazine field, ’What type of work does Dan do?’ They’d probably say that I’m a portrait photographer. But if you look at my body of work, I have deliberately tried to keep it very diverse.

If I had to shoot one type of subject matter exclusively, I’d imagine that it could lose some of it’s magic. I made a conscious decision early on to try to be as diverse as possible with regards to the subject matter. I think the word “style” implies a technique, a technical approach. if X, Y, and Z are in place then you get a certain kind of picture. I try to apply a sensibility to my approach so the consistencies come from the voice and not the technique. Having said that, photography, like many mediums is steeped in technique. It’s always a challenge. Everyone has their own take on subject matter. To a large degree I consider myself a journalist. I choose to do editorial work, and I always try to be aware of the magazine and the magazine’s editorial content. Honor the story. How can I augment the story, contribute to the story? How can I give the written word what it needs in a visual sense?

Seckler:: What’s your process for getting people to let their guard down and emote in front of the camera?

Winters: I usually like to sit with the person before I begin shooting to talk about what my expectations are, what the magazine’s expectations are, what I’m trying to accomplish. I tell them right off the bat, ‘don’t think of this as a photo shoot, this is a portrait session.’ And I think they’re so completely relieved, because typically when people do shoots, every frame that’s fired they feel like they’re supposed to do something. And there’s also a realization that if I get hired by the New York Times to do a cover, right off the bat there’s a mutual respect. The Times isn’t going to hire just anybody to shoot a cover. I’ve shot a lot of people multiple times. There’s also a whole connect that happens. There are often mutual friends involved. So there’s a familiarity that’s established.

Seckler: Once the subject is on set and you’re behind the camera, what is the process like?

Winters: I direct the whole thing. I will tell them exactly what I need, and I talk them through it. Chin up, eyes over here, do this, do that. My shoots are really short, usually. Sometimes I’ll shoot only thirty frames. I know what I want, usually, and it’s easy to get it if people allow me to direct them. I’ve done about thirty commercials and tons of music videos in my day and I have no problem directing. And I think it’s really easy for an actor, or anybody I’m shooting, to take direction, because like I said, they don’t feel like they need to be generating stuff for me. I’m telling them what I want.

Seckler: Aside from Will Ferrell what else have you been shooting recently?

Winters: I just did a portrait of Jonathan Franzen for a Time Magazine cover. The tagline is was to be, ‘America’s greatest novelist.’ He’s also a birdwatcher. And the magazine had asked for a bird watching photo. In my mind I didn’t know what that would be, and I started thinking, ‘wow, it would be really great if I could shoot handheld, and just figure out something that will work with him in the landscape.’ I didn’t really know what the picture was going to look like, but I had an idea that I wanted it to be expansive. It was in Santa Cruz. I’d driven around and found some spots that I felt would work. And we had driven up to UC Santa Cruz to shoot some environmental shots of his office.

On the way up to the school I saw on a hill, an old barn, and I thought, oh my God, I could never have imagined this. This is so beautiful. So when I saw that, I asked him, would you ever bird watch up here? And he said yes. And so this location, this opportunity, presented itself. I framed him very small in the frame, sitting down in the brush. And he’s almost really kind of not there. The idea of being a birdwatcher is that you blend into the environment so you can really observe. It worked out in a way that I couldn’t have imagined.

Seckler: Tell me about the personal work you’ve been working on.

Winters: Well, you know I have so many bodies of work. I think photography, like anything in life, is best served when you work within a place of consciousness and being really aware of what you’re doing. And having the dialog with yourself, that internal dialog, ‘why am I doing this?’ And I think if you can establish that, that’s probably the most important thing a photographer can do.

So what I’m working on right now are bodies of work that I’ve been working on for years. I’ve been shooting my son since he was born, and I’ve thousands of pictures of him. I’ve been working on a piece on New York for over twenty years. I’ve been doing a thing on American cities for probably fifteen or sixteen years. I photograph my wife. I have a project of collages that I’ve been working on for a long time. I have several different ones going, and I’m doing one on the Cold War now. I’ve been photographing honey bees with a scanning electron microscope. I’ve been printing honey as photograms on glass, caramelizing it and printing it in a darkroom on glass. A lot of diverse approaches to different subject matter.

Seckler: You’ve created an incredible body of work over the years, where does your drive and passion come from to keep creating?

Winters: Well, I guess you could argue that any profession or any life pursuit, regardless of what it is, if the individual puts everything they have into it, it’s a way that their passion is manifested in the physical world. It comes from the heart. I think we’re all here to express our passion. And creativity is just one way. An amazing surgeon, an amazing musician,an amazing housewife — if you do something with love and care and passion, that will manifest in some way. I think to express one’s passion is to sort of really soul search and understand that the stuff comes to you and channels through you. If a subject interests me, and I feel like there’s a photograph or a drawing or a collage application to it, it’s really interesting to me to grow by maybe trying to interpret it. Trying to see how I can contribute something to the physical realm, using this as a vehicle. Like you said, ‘why do people respond to your portraiture?’It’s because we’re all human. We can look at that person and have a cathartic experience that a whole bunch of other people can have at the same time. I tend to think about this stuff way more than “how” to take the picture…‘Why take the picture?’ People come and ask me to make pictures for them. Every single time I feel incredibly grateful that someone has asked me to do this, because it’s my true passion in life. Which is why I try so hard every time, and I try to bring as much as I can to it every single time. You make one photograph at a time and at the end of your life you look back and that’s your career.

Written by Zack Seckler

Edited by Greg Faherty

This piece was originally published 9/1/10 on Zack Seckler’s formally named publication The F STOP.

I’ve always been a Dan Winters fan so it’s a great pleasure to read this article about him. Thank you for doing this and Dan keep up your excellent work…always wanting to see more.

LikeLike

When I see this work I can’t help but be inspired that celeb portraiture isn’t just about making people look pretty and glam. They’re real people and they deserve to be photographed with the depth of Mr. Winters studied eye.

LikeLike

I don’t see what’s so special about setting up three lights and asking Tom Hanks to look off camera. He’s an actor, no kidding he can look mysterious and cool. I’m not really impressed. The set shots are kinda cool but the straight portraits bore me.

LikeLike

Great interview from a great photographer. Looks like Dan just did a rebuild of his site with a lot of new work!

LikeLike

The best thing about Dan, other than his work, is how eloquently he speaks about his work – that’s not always the case, and for me at least just as if not more difficult.

LikeLike

Oh yeah Travis, there are heaps of new images up on Dan’s website! I’ll never look at honey the same way again. Agreed with all of you here except RT…listen, if you could take pictures of Tom Hanks like that you could say something. Until then buzz off.

LikeLike

Very interesting article – Of course I love the discussion of Mr. Winter’s work and the process he goes through, especially with the Will Ferrell/Wired project. One concern though, and I wonder if it’s shared with anyone else – if some of Dan Winter’s caliber and stature in the industry is willing to go through so much work (Ferrell video proj. of Wired iPad issue) for either free or at reduced fees, aren’t magazines likely to expect the rest of regular schmoe photographers to do the same? I worry about the precedent.

Comments from other working shooters out there?

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this interview, love Mr. Winters’ work and an look into his process!

LikeLike

The shot of Tom Hanks is staggering…wow

LikeLike

The shot of Tom Hanks is staggeringly good…wow

LikeLike

I like most of Winters’ work, but I’ve never cared for the Laura Dern portrait. Maybe it’s the point, but that’s not who I think of when I remember her movies. It’s as if every detail was constructed to show the harshest, most unflattering angle possible.

LikeLike

I don’t know much about Dan Winters, except that the name sounds familiar. Portraits, some will like what others don’t. Even if I don’t love an image of his I can see the thought, atention to detail and mood that went into it.

As an artist I will do things that cost me personally. As a profesional I’d want Wiered to know they owe me big time! I think you have to have an existing relashionship to start doing corporate work where you give in a lot of extras for free or barter. Sad that Wiered couldn’t foot the bill totally, but he was breaking new ground, and to be able to do this project propperly was worth the investment.

So many photographers, I’ve worked for or with, can’t explain anything to either the model or themselves. So nice to read about some one who thinks things through on a philosophical level as well as a technical one.

Thanks, I look forward to more articales on this site.

LikeLike

Forgive my ignorance, but I never knew who Dan Winters was until I started following David Hobby’s Strobist blog.

And well, he’s ABSO-effin-LUTELY AWESOME! WOW! The photos on Winters’ site are a portrait photographers wet dream.

LikeLike

Mastery and eloquence.

I am humbled

and inspired.

LikeLike

I also knew Dan Winters through David Hobby’s Strobist blog.

What a great job Mr. Winter do. More than excellent. He uses perfection.

LikeLike

Inspiring work and interview!

LikeLike

Proof that there is something compelling in just being.

Big fan, good interview.. keep up the good work!

LikeLike

It’s always nice to see simple, stunning, classic portraiture that doesn’t rely on the fad of the day.

Cheers,

GuessTheLighting.com

LikeLike

Dan is the man! I first heard about him from school because he was coming to visit and it seemed like this guy was the real deal. He spoke and presented his work and the auditorium was overflowing with people and not enough seats. What I got from his visit.

1) He has no ego. Seems like the nicest and most sincere photographer anywhere. (He teared at the end because there was a standing ovation)

2) Im still amazed he builds his own sets, and shoots large and medium analog format

3) and he doesnt like to light ears.

Dan Winters is legendary.

LikeLike

Love the Tom Hanks portrait, Iconic

LikeLike

Thanks for letting me discover this photographer, truly inspiring work…

LikeLike

it’s a shame he was not asked about retouching. he shows the frame lines on many of this photos, as if to indicate they are not cropped or retouched, but I think they are actually heavily retouched and showing the frame edges of the film neg is misleading.

LikeLike

That Helen Miren shot is pretty amazing. Is that natural light or did he fake it?

LikeLike